Diagnosed Psycopath: A Mental Illness?

- lizlevert1

- Mar 7

- 3 min read

Up until the mid-1900s, asylums were the place for our irrational, erratic, and eclectic family members and the unwanted members of society. These people were described as “Crazy, Insane, Psychotic, Irrational, Quirky, etc.”—but no matter the label, they all went to the same place. Back then, there was less distinction between different mental illnesses and certainly none between mental illness and other disorders. The most common modern misdiagnosis seems to be the confusion between personality disorders and mental illness. This brings up an important question: Is a psychopath mentally ill?

Psychopathy is often confused with mental illness, but it is generally not classified as such. Psychopathy is a personality disorder, most often associated with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). While there are significant overlaps between personality disorders and mental illnesses, psychopathy is typically not seen as a mental illness.

Here’s why:

Psychopathy does not involve psychosis. Unlike conditions like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, psychopathy is not characterized by hallucinations, delusions, or mood dysregulation.

Psychopathy is rooted in personality and behavior patterns, making it different from conditions that affect brain chemistry or cognitive processes.

Psychopaths are fully aware of their actions and the consequences of their behavior, unlike individuals with severe mental illnesses who may lose touch with reality or struggle to control their actions due to their mental state.

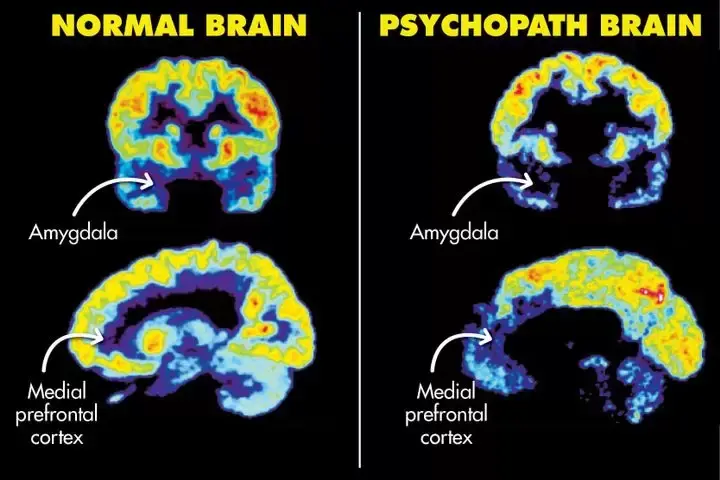

Beyond the sympotomatic differences, psychopathy and severe mental illnesses differ in affects on the brain. Research shows that psychopathy and severe mental illnesses impact the brain in distinct ways, particularly in areas that deal with emotion and decision-making. One of the major differences lies in brain structure.

For those with psychopathy, imaging studies have revealed that:

There is reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex, especially the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which is involved in impulse control and moral decision-making.

The amygdala, a region crucial for emotional processing and empathy, is smaller and less active in psychopaths.

There is reduced connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, which makes it difficult for psychopaths to regulate emotions or control aggressive impulses.

In contrast, severe mental illness often leads to:

Widespread gray matter loss in the frontal and temporal lobes, areas that are responsible for higher cognitive functions like thinking, planning, and decision-making.

Enlarged ventricles, indicating a loss of brain tissue, especially in conditions like schizophrenia.

White matter abnormalities, which impact communication between brain regions, leading to cognitive disorganization, particularly in conditions like bipolar disorder.

Beyond brain structure, the functional differences in how the brain works are also profound.

In psychopathy:

The amygdala shows decreased activity, making it difficult for psychopaths to feel fear, guilt, or empathy.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (involved in impulse control and moral reasoning) is hypoactive, which contributes to poor decision-making and lack of moral judgment.

The reward system (particularly the striatum) is overactive, which explains the psychopath’s inclination toward risk-taking and sensation-seeking behaviors.

In severe mental illness:

Schizophrenia involves dysfunction in the dopamine system, leading to overactivity in the mesolimbic pathway, which is associated with hallucinations and delusions.

Bipolar disorder often shows overactivity in the limbic system, contributing to extreme mood swings, particularly during manic episodes.

Disorganized brain network connectivity is common in schizophrenia, causing cognitive fragmentation and difficulty distinguishing between reality and delusions.

The emotional and behavioral impacts of psychopathy and severe mental illness are also quite different. Psychopaths typically lack the ability to feel fear, guilt, or empathy, which makes them prone to manipulative, impulsive, and sometimes violent behavior. They may appear charming, but they often use others for personal gain, showing little remorse for their actions.

In contrast, individuals with severe mental illness, like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, often experience intense emotional episodes. For example, those with schizophrenia may experience hallucinations and delusions that distort their perception of reality. Bipolar disorder can lead to extreme mood swings from deep depression to manic episodes marked by erratic behavior and impulsivity.

If we are going to reduce the stigma around severe mental illness and truly help those in need, it is essential to recognize that mental illness is not a singular condition with one universal experience. There is no single definition of "crazy," and lumping all disorders together only perpetuates misunderstandings and hinders effective treatment.

We must stop treating individuals with severe mental illness as though they can simply control their symptoms. Instead, we need to invest in more research to uncover the underlying causes of these disorders and ultimately find a cure. By acknowledging the complexities of severe mental illness while also recognizing the unique challenges of treating psychopathy, we can foster greater public awareness and develop better support systems for those who need them most.

Comments